The stereotyping of the Orient and its inhabitants by Western Europeans is well visible in their eyes to Bulgarian women.

A good example is the article by Hester Donaldson Jenkins, an American teacher and missionary, in the National Geographic Magazine, where she described the Bulgarian students at the American College of Girls in Istanbul (1915). By comparing them with the other “orientations” in the school (Greek, Armenian, and Turkish), she found similar but different characteristics:

Among the oriental girls with whom I lived in my nine years’ residence in the near East, none interested me more than the Bulgarians. They are, perhaps, the least oriental of the eight or more nationalities to be found in the Constantinople college, of which I was a professor. They are fairer and brighter in coloring than the Armenians, Greeks or Persians, rather taller and larger on an average, and have far more energy and less languor than the Turk.

The Bulgarian girls distinguished themselves from the others by a certain wholesome, out-of-door quality, a sanity which marked them sharply from the fanciful, sentimental and weaker-nerved girls of some of the other nationalities.

Bulgarian girls incline to roundness of contour and figure, many of them having round, full faces, ripe, rosy mouths, and dimples. This effect Is heightened by the fashion of wearing the hair in braids wound about the head. One sees plenty of dark hair In Bulgaria, but one also looks with pleasure on warm brown tints, chestnut tresses, and occasionally auburn heads. One of the most beautiful girls I ever saw was a Bulgarian, with a glorious mass of copperoolored waves, a clear, pale skin, handsomely set gray eyes, a delicate mouth, and small, white teeth, and the height and carriage of a princess.

The bright cheeks that so many of the Bulgarians have are a pleasant change from the dark or pale skins of the Armenians and Greeks. Their eyes are generally less large and languorous than oriental eyes, looking you squarely In the face, with more frankness and less seduction.

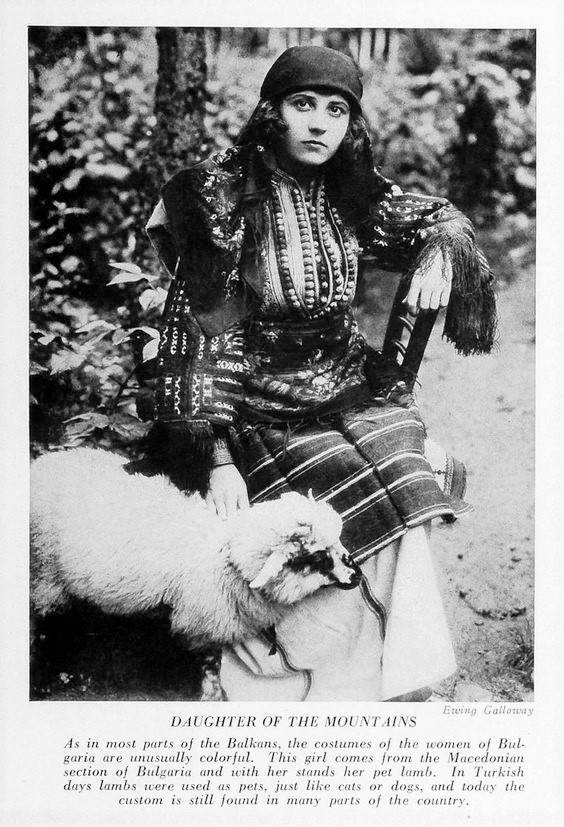

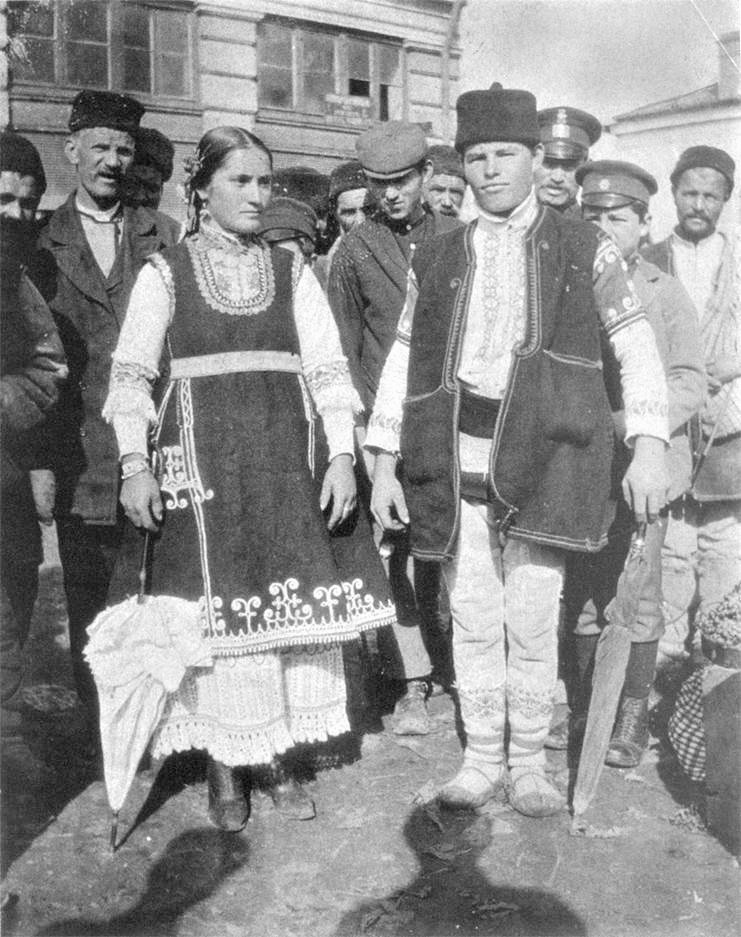

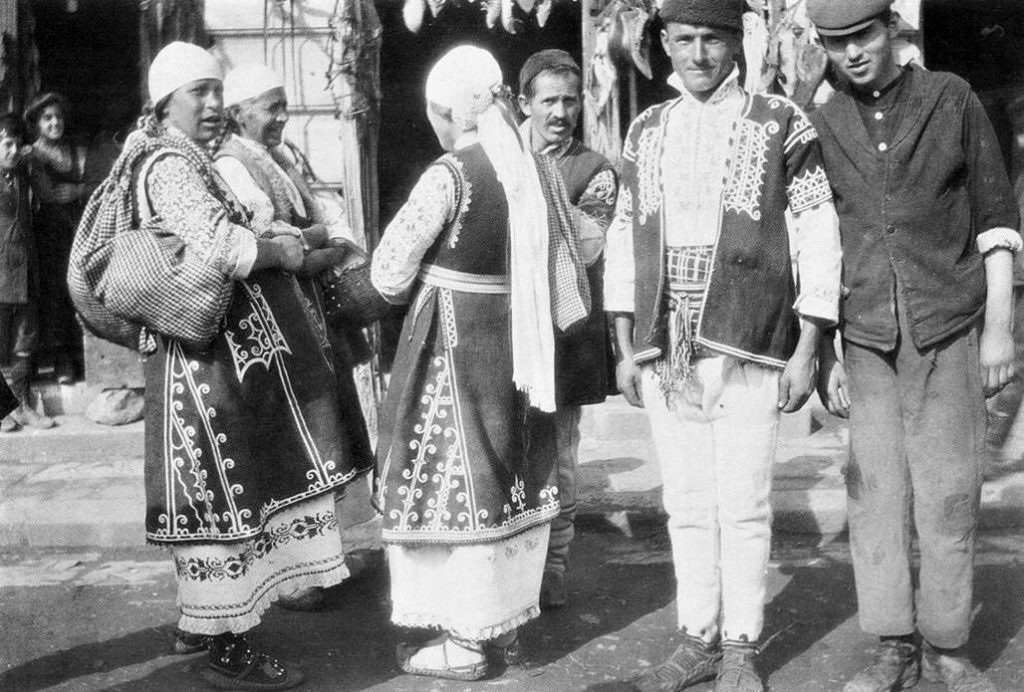

Bulgarian girls are bright dressers. The village holiday brings out a wonderful array of gaudy costumes, stralgbt and awkward In line, but brilliant In color and decoration, the writer tells. The women’s big waists are usually emphasized by huge silver buckles Wlimi, however, a girl rs young and pretty, her abundant, curly balr Into which ure braided bright threads or ribbons, with often a flower in her ear, her bright color heightened by the gay embroideries, and her slender figure, which tho stralghtness Of her dress cannot spoil, make her an attractive vision.

A girl in a Bulgarian village Is not without her amusements. As In the Bible times, all the water for a village must be drawn from one or two wells or springs, and these watering places or fountains are the scene of mucli sociability. Hither come all the youths and maidens of the village to loiter. There is coquetting and courting about the fountain and home gatherings in the evenings. Marriages spring from mutual attraction and choice, rather than the arrangement of families, as do the Armenian and Turkish alliances.

There are husking bees and quiltIng bees where the young people meet, but the most popular form of social entertainment is the sedanka. Here assemble the young men and women of the village and adjoining farms, grouped about an open fire, singing solos and choruses. The Bulgarian folk dances are danced in a row or circle, the leader generally waving a bright handkerchief and turning and twisting about his line of followers, like a mild game of ‘snap the whip.’ It suggests health and abounding spirits and good fellowship, without the sensuality that so often marks the oriental dance.

Occasionally the sedanka ends in a dramatic fashion. Some brawny fellow who has been courting his Darka assiduously will seize her In his arms and carry her to his home. The next day this marriage by capture’ is given legal and religious sanction by the blessing of the Orthodox priest. I once asked Zarafinka what would happen If two men wanted the same girl. She replied simply The stronger would get her.’

The Bulgarian girls are bright and make eager use of educational advantages. The collegetrained Bulgar maidens become veritable centers of progress in the towns and villagesithroughout their country, Instilling the hunger for knowledge that, in turn, is to lead Bulgaria a great future. (Hester Donaldson Jenkins “Bulgaria and its Women,” the National Geographic Magazine, April, 1915)

This view of the Bulgarians is also visible to the foreign photographers and artists who worked in the country in the first half of the 20th century. They draw with ethnographic accuracy the Bulgarian folk costumes, rituals and customs, they were looking to paint or capture the colorful issues and exotic places, as markets, remains of ancient buildings, or minorities (mostly gypsies).